from Chel Avery

![story hour story hour]() Over the holiday season, I found myself thinking a lot about how our lives are filled with story. We are packing up now from a period that is rich in story―the story of a baby’s birth in humble circumstances, the story of light’s persistence in a newly dedicated temple, the story of the sun’s return in a season of darkness, and many more―all tales of light and miracles. I have been musing about how important stories are, how stories stitch together our culture and give us a way to exchange meaning about so many things.

The best and most important stories are told and retold, endlessly offering new insight, or ways to express new ideas within a familiar backdrop. I once read a book for pastors describing approaches to resolving conflict in a congregation. The author framed his perspective through the story of the prodigal son―retellng the familiar tale from the point of view of the son, of the son’s older brother, and of the father of two valued but very different sons. A single story provided a framework for many approaches to a subject―a shared, familiar, and quickly recognizable framework.

Quakers have our own set of stories that we tell frequently as a way of explaining our identity. All these stories come in many versions and we use them to say to each other who we are, who we aspire to be, how we want to be seen by others. We have the stories of the children of Reading, of Thomas Lurting and the pirates, of the footwashing at Marlborough, and of Quaker settlers propping their muskets outside their houses at night to signal their peaceful intent to the Indians. A most familiar story is the one about George Fox telling William Penn to “wear thy sword as long as thou canst,” almost certainly untrue, as historian Paul Buckley has taken trouble to research, but greatly expressive for modern Friends.

Our stories get us in trouble when we forget that no story is ever “the whole story,” or when we conflate our stories with actual history. When conflict broke out between formerly peaceful ethnic groups in the Balkans in the 1990s, an observer noted how almost overnight there were dramatic changes in the telling of each group’s centuries-old stories about themselves as a people. It wasn’t the elements of stories that changed so much as how they were punctuated: What was cause, what was effect? At what point does an episode begin and where does it end? What is foreground, what is background? Simply by re-punctuating their stories, ethnic groups were able find meanings that framed one group as innocent, another as guilty or threatening.

Over the holiday season, I found myself thinking a lot about how our lives are filled with story. We are packing up now from a period that is rich in story―the story of a baby’s birth in humble circumstances, the story of light’s persistence in a newly dedicated temple, the story of the sun’s return in a season of darkness, and many more―all tales of light and miracles. I have been musing about how important stories are, how stories stitch together our culture and give us a way to exchange meaning about so many things.

The best and most important stories are told and retold, endlessly offering new insight, or ways to express new ideas within a familiar backdrop. I once read a book for pastors describing approaches to resolving conflict in a congregation. The author framed his perspective through the story of the prodigal son―retellng the familiar tale from the point of view of the son, of the son’s older brother, and of the father of two valued but very different sons. A single story provided a framework for many approaches to a subject―a shared, familiar, and quickly recognizable framework.

Quakers have our own set of stories that we tell frequently as a way of explaining our identity. All these stories come in many versions and we use them to say to each other who we are, who we aspire to be, how we want to be seen by others. We have the stories of the children of Reading, of Thomas Lurting and the pirates, of the footwashing at Marlborough, and of Quaker settlers propping their muskets outside their houses at night to signal their peaceful intent to the Indians. A most familiar story is the one about George Fox telling William Penn to “wear thy sword as long as thou canst,” almost certainly untrue, as historian Paul Buckley has taken trouble to research, but greatly expressive for modern Friends.

Our stories get us in trouble when we forget that no story is ever “the whole story,” or when we conflate our stories with actual history. When conflict broke out between formerly peaceful ethnic groups in the Balkans in the 1990s, an observer noted how almost overnight there were dramatic changes in the telling of each group’s centuries-old stories about themselves as a people. It wasn’t the elements of stories that changed so much as how they were punctuated: What was cause, what was effect? At what point does an episode begin and where does it end? What is foreground, what is background? Simply by re-punctuating their stories, ethnic groups were able find meanings that framed one group as innocent, another as guilty or threatening.

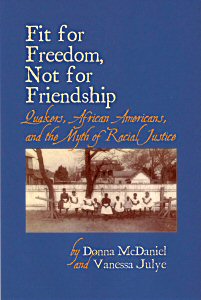

![FfF FfF]() Quakers have sometimes been called to examine and even relearn our stories, such as our frequently told tales of Quaker work on the underground railroad and Quaker support of abolition. It is not that these stories are false, but that in telling them as our history, and in leaving out other parts of our past, we create an image of ourselves that is incomplete and blinds us to the larger picture. When this happens, we need such books as Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship to fill in the forgotten parts of our record.

Stories can be powerful. Stories can be dangerous. Stories can be inspirational. Stories are shared identity. And always, stories are absolutely necessary.

Quakers have sometimes been called to examine and even relearn our stories, such as our frequently told tales of Quaker work on the underground railroad and Quaker support of abolition. It is not that these stories are false, but that in telling them as our history, and in leaving out other parts of our past, we create an image of ourselves that is incomplete and blinds us to the larger picture. When this happens, we need such books as Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship to fill in the forgotten parts of our record.

Stories can be powerful. Stories can be dangerous. Stories can be inspirational. Stories are shared identity. And always, stories are absolutely necessary.

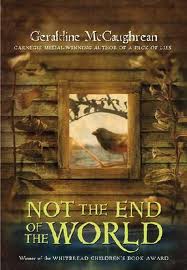

![Ark 2 Ark 2]() One of my favorite kinds of fiction is the retelling of a familiar story in a way that invites readers to understand it differently. One such story continues to haunt me. I’ve written before about Not the End of the World, which tells the voyage of Noah’s family on the ark from the perspective of Noah’s young daughter. This is a troubling but ultimately satisfying interpretation of a well known tale. Although the book is written for young adults, I recommend it for older readers. The good news is that the price is greatly reduced ($2). The bad news is that we have only five remaining copies and are unlikely to be able to get more.

One of my favorite kinds of fiction is the retelling of a familiar story in a way that invites readers to understand it differently. One such story continues to haunt me. I’ve written before about Not the End of the World, which tells the voyage of Noah’s family on the ark from the perspective of Noah’s young daughter. This is a troubling but ultimately satisfying interpretation of a well known tale. Although the book is written for young adults, I recommend it for older readers. The good news is that the price is greatly reduced ($2). The bad news is that we have only five remaining copies and are unlikely to be able to get more.

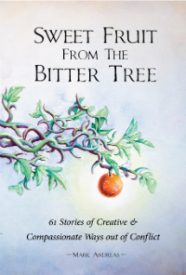

![sweet fruit sweet fruit]() Some writers use stories quite deliberately as tools to help readers imagine possibilities. A recent collection from Earlham grad Mark Andreas assembles real people’s stories about creative ways they found to navigate conflict in a wide variety of situations, ranging from street crime to jailbreaks to human resources issues in organizations. Sweet Fruit from the Bitter Tree is fun to read, trying to imagine how each narrator will turn around what initially appears to be an impossible situation.

Some writers use stories quite deliberately as tools to help readers imagine possibilities. A recent collection from Earlham grad Mark Andreas assembles real people’s stories about creative ways they found to navigate conflict in a wide variety of situations, ranging from street crime to jailbreaks to human resources issues in organizations. Sweet Fruit from the Bitter Tree is fun to read, trying to imagine how each narrator will turn around what initially appears to be an impossible situation.

![candles candles]() A similar book for children is our own classic Lighting Candles in the Dark. It contains sections of stories on courage and nonviolence, on the power of love, on service, on fairness and equality, and on care for the earth. This book is currently out of print in paper but you can dowload a digital version for your ereader, computer, or other device.

A similar book for children is our own classic Lighting Candles in the Dark. It contains sections of stories on courage and nonviolence, on the power of love, on service, on fairness and equality, and on care for the earth. This book is currently out of print in paper but you can dowload a digital version for your ereader, computer, or other device.

![journeys journeys]() Another book for children assembles stories that together present the story of Quakers as a people. Journeys in the Light contains both fictional stories typical of Friends and dramatizations of real events involving Quakers over the centuries and from around the world expressing peace, simplicity, truth, and equality in their lives.

Another book for children assembles stories that together present the story of Quakers as a people. Journeys in the Light contains both fictional stories typical of Friends and dramatizations of real events involving Quakers over the centuries and from around the world expressing peace, simplicity, truth, and equality in their lives.

![not one damsel not one damsel]() Finally, a great book especially for girls is Not One Damsel in Distress which assembles folktales from around the world showring girls as strong, active heroes in charge of their own destinies. Stories come from Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

May this story and the next one end happily ever after.

Chel

Finally, a great book especially for girls is Not One Damsel in Distress which assembles folktales from around the world showring girls as strong, active heroes in charge of their own destinies. Stories come from Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

May this story and the next one end happily ever after.

Chel

Over the holiday season, I found myself thinking a lot about how our lives are filled with story. We are packing up now from a period that is rich in story―the story of a baby’s birth in humble circumstances, the story of light’s persistence in a newly dedicated temple, the story of the sun’s return in a season of darkness, and many more―all tales of light and miracles. I have been musing about how important stories are, how stories stitch together our culture and give us a way to exchange meaning about so many things.

The best and most important stories are told and retold, endlessly offering new insight, or ways to express new ideas within a familiar backdrop. I once read a book for pastors describing approaches to resolving conflict in a congregation. The author framed his perspective through the story of the prodigal son―retellng the familiar tale from the point of view of the son, of the son’s older brother, and of the father of two valued but very different sons. A single story provided a framework for many approaches to a subject―a shared, familiar, and quickly recognizable framework.

Quakers have our own set of stories that we tell frequently as a way of explaining our identity. All these stories come in many versions and we use them to say to each other who we are, who we aspire to be, how we want to be seen by others. We have the stories of the children of Reading, of Thomas Lurting and the pirates, of the footwashing at Marlborough, and of Quaker settlers propping their muskets outside their houses at night to signal their peaceful intent to the Indians. A most familiar story is the one about George Fox telling William Penn to “wear thy sword as long as thou canst,” almost certainly untrue, as historian Paul Buckley has taken trouble to research, but greatly expressive for modern Friends.

Our stories get us in trouble when we forget that no story is ever “the whole story,” or when we conflate our stories with actual history. When conflict broke out between formerly peaceful ethnic groups in the Balkans in the 1990s, an observer noted how almost overnight there were dramatic changes in the telling of each group’s centuries-old stories about themselves as a people. It wasn’t the elements of stories that changed so much as how they were punctuated: What was cause, what was effect? At what point does an episode begin and where does it end? What is foreground, what is background? Simply by re-punctuating their stories, ethnic groups were able find meanings that framed one group as innocent, another as guilty or threatening.

Over the holiday season, I found myself thinking a lot about how our lives are filled with story. We are packing up now from a period that is rich in story―the story of a baby’s birth in humble circumstances, the story of light’s persistence in a newly dedicated temple, the story of the sun’s return in a season of darkness, and many more―all tales of light and miracles. I have been musing about how important stories are, how stories stitch together our culture and give us a way to exchange meaning about so many things.

The best and most important stories are told and retold, endlessly offering new insight, or ways to express new ideas within a familiar backdrop. I once read a book for pastors describing approaches to resolving conflict in a congregation. The author framed his perspective through the story of the prodigal son―retellng the familiar tale from the point of view of the son, of the son’s older brother, and of the father of two valued but very different sons. A single story provided a framework for many approaches to a subject―a shared, familiar, and quickly recognizable framework.

Quakers have our own set of stories that we tell frequently as a way of explaining our identity. All these stories come in many versions and we use them to say to each other who we are, who we aspire to be, how we want to be seen by others. We have the stories of the children of Reading, of Thomas Lurting and the pirates, of the footwashing at Marlborough, and of Quaker settlers propping their muskets outside their houses at night to signal their peaceful intent to the Indians. A most familiar story is the one about George Fox telling William Penn to “wear thy sword as long as thou canst,” almost certainly untrue, as historian Paul Buckley has taken trouble to research, but greatly expressive for modern Friends.

Our stories get us in trouble when we forget that no story is ever “the whole story,” or when we conflate our stories with actual history. When conflict broke out between formerly peaceful ethnic groups in the Balkans in the 1990s, an observer noted how almost overnight there were dramatic changes in the telling of each group’s centuries-old stories about themselves as a people. It wasn’t the elements of stories that changed so much as how they were punctuated: What was cause, what was effect? At what point does an episode begin and where does it end? What is foreground, what is background? Simply by re-punctuating their stories, ethnic groups were able find meanings that framed one group as innocent, another as guilty or threatening.

Quakers have sometimes been called to examine and even relearn our stories, such as our frequently told tales of Quaker work on the underground railroad and Quaker support of abolition. It is not that these stories are false, but that in telling them as our history, and in leaving out other parts of our past, we create an image of ourselves that is incomplete and blinds us to the larger picture. When this happens, we need such books as Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship to fill in the forgotten parts of our record.

Stories can be powerful. Stories can be dangerous. Stories can be inspirational. Stories are shared identity. And always, stories are absolutely necessary.

Quakers have sometimes been called to examine and even relearn our stories, such as our frequently told tales of Quaker work on the underground railroad and Quaker support of abolition. It is not that these stories are false, but that in telling them as our history, and in leaving out other parts of our past, we create an image of ourselves that is incomplete and blinds us to the larger picture. When this happens, we need such books as Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship to fill in the forgotten parts of our record.

Stories can be powerful. Stories can be dangerous. Stories can be inspirational. Stories are shared identity. And always, stories are absolutely necessary.

One of my favorite kinds of fiction is the retelling of a familiar story in a way that invites readers to understand it differently. One such story continues to haunt me. I’ve written before about Not the End of the World, which tells the voyage of Noah’s family on the ark from the perspective of Noah’s young daughter. This is a troubling but ultimately satisfying interpretation of a well known tale. Although the book is written for young adults, I recommend it for older readers. The good news is that the price is greatly reduced ($2). The bad news is that we have only five remaining copies and are unlikely to be able to get more.

One of my favorite kinds of fiction is the retelling of a familiar story in a way that invites readers to understand it differently. One such story continues to haunt me. I’ve written before about Not the End of the World, which tells the voyage of Noah’s family on the ark from the perspective of Noah’s young daughter. This is a troubling but ultimately satisfying interpretation of a well known tale. Although the book is written for young adults, I recommend it for older readers. The good news is that the price is greatly reduced ($2). The bad news is that we have only five remaining copies and are unlikely to be able to get more.

Some writers use stories quite deliberately as tools to help readers imagine possibilities. A recent collection from Earlham grad Mark Andreas assembles real people’s stories about creative ways they found to navigate conflict in a wide variety of situations, ranging from street crime to jailbreaks to human resources issues in organizations. Sweet Fruit from the Bitter Tree is fun to read, trying to imagine how each narrator will turn around what initially appears to be an impossible situation.

Some writers use stories quite deliberately as tools to help readers imagine possibilities. A recent collection from Earlham grad Mark Andreas assembles real people’s stories about creative ways they found to navigate conflict in a wide variety of situations, ranging from street crime to jailbreaks to human resources issues in organizations. Sweet Fruit from the Bitter Tree is fun to read, trying to imagine how each narrator will turn around what initially appears to be an impossible situation.

A similar book for children is our own classic Lighting Candles in the Dark. It contains sections of stories on courage and nonviolence, on the power of love, on service, on fairness and equality, and on care for the earth. This book is currently out of print in paper but you can dowload a digital version for your ereader, computer, or other device.

A similar book for children is our own classic Lighting Candles in the Dark. It contains sections of stories on courage and nonviolence, on the power of love, on service, on fairness and equality, and on care for the earth. This book is currently out of print in paper but you can dowload a digital version for your ereader, computer, or other device.

Another book for children assembles stories that together present the story of Quakers as a people. Journeys in the Light contains both fictional stories typical of Friends and dramatizations of real events involving Quakers over the centuries and from around the world expressing peace, simplicity, truth, and equality in their lives.

Another book for children assembles stories that together present the story of Quakers as a people. Journeys in the Light contains both fictional stories typical of Friends and dramatizations of real events involving Quakers over the centuries and from around the world expressing peace, simplicity, truth, and equality in their lives.

Finally, a great book especially for girls is Not One Damsel in Distress which assembles folktales from around the world showring girls as strong, active heroes in charge of their own destinies. Stories come from Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

May this story and the next one end happily ever after.

Chel

Finally, a great book especially for girls is Not One Damsel in Distress which assembles folktales from around the world showring girls as strong, active heroes in charge of their own destinies. Stories come from Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

May this story and the next one end happily ever after.

Chel